For ARCOmadrid 2024, Almeida & Dale is honored to present the sacred geometry of Rubem Valentim in a remarkable set of paintings, sculptures, graphic works and reliefs that demonstrate the visual and poetic richness of his production. A learned and deeply spiritual person, Valentim (Salvador, Bahia, 1922 − São Paulo, São Paulo, 1991) led his artistic career along a path of introspection. Closely linked to his inner life, his art translates Black Brazilian cultural roots, particularly the rich imagery of African diasporic religions such as Candomblé and Umbanda, in an original and inventive way.

![Emblema-84 [Emblem-84], 1984](https://api.almeidaedale.com.br/uploads/w_1500,f_webp,q_80/0074_A_and_D_031808_FRENTE_5ec65ddc09.jpg)

Emblema-84 [Emblem-84], 1984

Acrylic on canvas

50 x 70 cm [19 ¾ x 27 ½ in]

![Emblema-78 [Emblem-78], 1978](https://api.almeidaedale.com.br/uploads/w_1500,f_webp,q_80/9513_FRENTE_2f2df05325.jpg)

Emblema-78 [Emblem-78], 1978

Acrylic on canvas

73 x 100 cm [28 ¾ x 39 ⅜ in]

![Relêvo Emblema-79 [Emblem Relief-79], 1979](https://api.almeidaedale.com.br/uploads/w_1500,f_webp,q_80/1980_A_and_D_011961_FRENTE_118a1dbe92.jpg)

Relêvo Emblema-79 [Emblem Relief-79], 1979

Acrylic on wood

50 x 70 x 7 cm [19 ¾ x 27 ½ x 2 ¾ in]

“In Brazil, the work of Bahia native Rubem Valentim eloquently illustrates the productive currents flowing to and from African, Brazilian, and European contexts. Valentim’s approach was anthropophagic, combining Constructivism with references from the Afro-Brazilian religious universe”.

Adriano Pedrosa and Tomás Toledo. "Afro-Atlantic Histories" catalogue, MASP, 2018

![Emblema-85 [Emblem-85], 1985](https://api.almeidaedale.com.br/uploads/w_1500,f_webp,q_80/0068_image_6b3421bbaa.jpg)

Emblema-85 [Emblem-85], 1985

Acrylic on canvas

50 x 35 cm [19 ¾ x 13 ¾ in]

![Emblema-84 [Emblem-84], 1984](https://api.almeidaedale.com.br/uploads/w_1500,f_webp,q_80/1242_A_and_D_081882_FRENTE_aa15238583.jpg)

Emblema-84 [Emblem-84], 1984

Acrylic on canvas

27 x 41 cm [10 ⅝ x 16 ⅛ in]

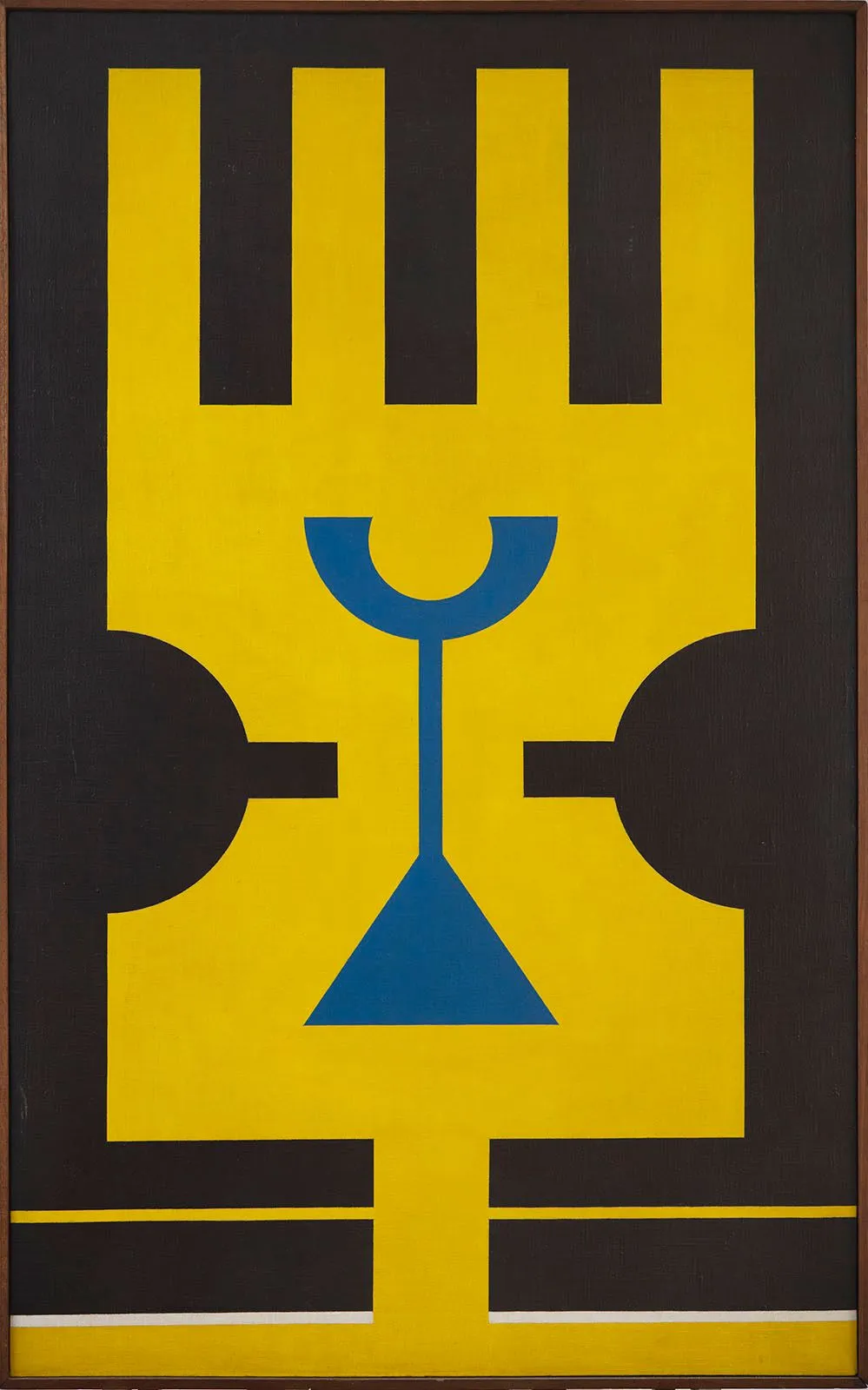

The works on display at ARCOmadrid 2024 reveal the rich repertory of motifs Valentim often resorted to and mixed in different ways to construct emblems that function as equations. They combine basic geometric shapes − triangles, rectangles, circles, trapezoids − and figures created from a sober transformation of Candomblé images, tools and signs, such as the oxê, Xangô’s double axe − which became a kind of logo in his work; Exu’s trident; Oxalá’s sceptre, called opaxorô; and other elements from the Yoruba tradition.

![Emblema-1986 [Emblem-1986], 1986](https://api.almeidaedale.com.br/uploads/w_1500,f_webp,q_80/1690_principal_b7852c3628.jpg)

Emblema-1986 [Emblem-1986], 1986

Acrylic on paper

70 x 50 cm [27 ½ x 19 ¾ in]

![Emblema 85 [Emblem 85], 1985](https://api.almeidaedale.com.br/uploads/w_1500,f_webp,q_80/3870_principal_96f86ac61b.jpg)

Emblema 85 [Emblem 85], 1985

Acrylic on canvas

50 x 35 cm [19 ¾ x 13 ¾ in]

![Emblema 85 [Emblem 85], 1985](https://api.almeidaedale.com.br/uploads/w_1500,f_webp,q_80/10229_principal_4fa10368b7.jpg)

Emblema 85 [Emblem 85], 1985

Acrylic on canvas

41 x 33 cm [16 ⅛ x 13 in]

![Emblema-85 [Emblem-85], 1985](https://api.almeidaedale.com.br/uploads/w_1500,f_webp,q_80/0037_MG_3278_FRENTE_1d43f35a17.jpg)

Emblema-85 [Emblem-85], 1985

Acrylic on canvas

41 x 27 cm [16 ⅛ x 10 ⅝ in]

“The journey of the Obá Rubem Valentim, obsessively dedicated to the Orixás, is one of the most faithful among those dedicated to Brazilian art”.

Paulo Herkenhoff. “Rubem Valentim’s Lighting Stone, Oba Painter of House of Mae Senhora”, 23rd Bienal de São Paulo catalogue, 1996 (read the article here)

Untitled, n.d.

Wood

50 x 50 x 30 cm [19 ¾ x 19 ¾ x 11 ¾ in]

The reliefs and sculptures gathered for ARCOmadrid 2024 demonstrate the constant renewal of Valentim’s work, which followed his geographical displacements and the expansion of his visual repertoire. While living in Brasilia, Valentim responded to the spatial stimulus exerted by the new capital’s urban design, which impacted his creative process. The works came to occupy the space in a different way and, with their presence charged with sacredness, they function as altars.

![Conjunto Altar Sacral Emblemático - E59 [Emblematic Sacral Altar Set - E59], 1980](https://api.almeidaedale.com.br/uploads/w_1500,f_webp,q_80/1975_A_and_D_011975_C_59fed01552.png)

Conjunto Altar Sacral Emblemático - E59 [Emblematic Sacral Altar Set - E59], 1980

Wood

71 x 24 x 24 cm [28 x 9 ½ x 9 ½ in]

![Escultura II [Sculpture II], 1978](https://api.almeidaedale.com.br/uploads/w_1500,f_webp,q_80/5351_0120_A_49062c1307.png)

Escultura II [Sculpture II], 1978

Acrylic on wood

54 x 38 x 38 cm [21 ¼ x 15 x 15 in]

The totem-like wooden sculptures, which can be exhibited individually or in sets, represent a phase of Valentim’s work in which he explored the idea of monumentality.

![Objeto místico [Mystical object], 1972](https://api.almeidaedale.com.br/uploads/w_1500,f_webp,q_80/0471_A_and_D_031841_B_e2a9de4d93.png)

Objeto místico [Mystical object], 1972

Polychrome wood

26 x 21 x 7 cm [10 ¼ x 8 ¼ x 2 ¾ in]

“My art has an intrinsic monumental sense. It comes from the rite, from the party. It seeks the roots and it could find them in space, as a kind of resocialization of art, belonging to the people. It is the same monumentality as the totems, a point of reference for the entire tribe. My reliefs and objects fundamentally ask for space. I would like to integrate them into urban, architectural, and landscape spaces”.

Rubem Valentim. "Manifesto ainda que tardio” [A Manifesto, Albeit Late], 1976 (read the text here)

Objeto Emblemático 1, 1975

Polychrome wood

198 x 109 x 77 cm [78 x 42 ⅞ x 30 ¼ in]

The quality and relevance of Rubem Valentim’s work were widely recognized throughout his lifetime, and he participated in major collective exhibitions, such as La Biennale di Venezia, in 1962; several editions of the Bienal de São Paulo, from 1955 to the 2020s, including the 35th edition, in 2023; and the First World Festival of Black Arts in Senegal, in 1966.

Rubem Valentim’s work is part of major institutional collections in Brazil and abroad, such as Museu Afro Brasil Emanoel Araújo, Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo, Museu de Arte Moderna da Bahia, Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo – MAM SP, Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand - MASP, Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, Museum of Modern Art - MoMA, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Moderna di Roma, Colección Patrícia Phelps de Cisneros, Centre Pompidou, Tate, the Minneapolis Institute of Art, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, and others.

Exhibition "A Estética do Candomblé" [The Candomblé Esthetics], MAC-USP, São Paulo, 1989. Rubem Valentim Institute Archive. Photo: Rubens Fernandes

Among the recent exhibitions celebrating the artist and introducing him to contemporary audiences is "Rubem Valentim: Afro-Atlantic Constructions", 2018-2019, at MASP, which covers his production from 1955, when, still in Salvador, Valentim decidedly took on his references to Candomblé and Afro-Brazilian culture, until 1978.

Rubem Valentim’s works at MASP's "Picture Gallery in Transformation" (left and right)

After the show, two of his works were added to MASP's "Picture Gallery in Transformation" on the second floor of the museum, which puts in relation the most important works in the collection through Lina Bo Bardi's striking expography.

“Valentim is one of the artists who undertook the anthropophagic project in its most complete and ambitious way. In this process, he carried out one of the most radical operations in the history of Brazilian art, subjecting the European language to an Afro-Brazilian language in a contribution that was effectively singular and powerful, decolonizing and anthropophagic”.

Fernando Oliva. "Rubem Valentim: Afro-Atlantic Constructions" catalogue, MASP, 2018

![Emblema-86 [Emblem-86], 1986](https://api.almeidaedale.com.br/uploads/w_1500,f_webp,q_80/1754_A_and_D_031903_FRENTE_31eecfa897.jpg)

Emblema-86 [Emblem-86], 1986

Acrylic on canvas

50 x 35 cm [19 ¾ x 13 ¾ in]

![Emblema-87 [Emblem-87], 1987](https://api.almeidaedale.com.br/uploads/w_1500,f_webp,q_80/1755_A_and_D_031904_FRENTE_05a73ed62a.jpg)

Emblema-87 [Emblem-87], 1987

Acrylic on canvas

70 x 50 cm [27 ½ x 19 ¾ in]

![Emblema 88 [Emblem 88], 1988](https://api.almeidaedale.com.br/uploads/w_1500,f_webp,q_80/13790_FRENTE_637c0e4a95.jpg)

Emblema 88 [Emblem 88], 1988

Acrylic on canvas

50 x 35 cm [19 ¾ x 13 ¾ in]

Emphasizing Valentim's international recognition, "Emblema 70 n.2", 1970 has been integrating the long-term exhibition "A View from São Paulo: Abstraction and Society", at Tate Modern, since 2022. (see the artwork here)

![Emblema-70 [Emblem-70], nº2](https://api.almeidaedale.com.br/uploads/w_1500,f_webp,q_80/1400_A_and_D_091839_FRENTE_367a1c9ee3.jpg)

Emblema-70 [Emblem-70], nº2

Acrylic on canvas

121 x 73 cm [47 ⅝ x 28 ¾ in]

Also in 2022, Almeida & Dale produced the exhibition "Ilê Funfun: A Tribute to the Centenary of Rubem Valentim" (see the exhibit here)

Trailer for the exhibit "Ilê Funfun: A Tribute to the Centenary of Rubem Valentim"

Curated by Daniel Rangel, it brought together the essentials of Valentim’s trajectory: a powerful artistic-sacred art ensemble and references from his particular universe, as well as works from the collections of the Museu de Arte Moderna da Bahia, the Rubem Valentim Institute, and the Museu de Arte de Brasília.

Ilê means house and Terreiro (the sacred place where Candomblé’s rituals take place), the sacred temple of worship to the Orixás, and Funfun, the color white, a reference to those who dress in white, especially the family of Oxalufã, the old Oxalá, and Oxaguiã, the young Oxalá. “In truth, we are all children of Oxalá, entrusted by Olódùmarè to create all living beings on the planet, including plants, animals, men and women”, explained the curator Daniel Rangel.

The retrospective was presented in three sections: the “Temple of Oxalá”, a set of works with 20 sculptures and 10 reliefs; “Atelier”, where the artist's creative process was unveiled, bringing unfinished canvases that were in production at the time of his death in 1991, and tools he used; and “Chronology”, which resumed his history from clippings, research, documents and personal files, photographs and posters.

View of the section "Chronology", from the exhibition "Ilê Funfun", at Almeida & Dale, 2022

After the exhibition at Almeida & Dale, the show traveled on to the Museu Nacional da República, in Brasília, then returned to MAM Bahia, for the reopening of the Special Room dedicated to Rubem Valentim at the museum. Also commemorating the artist, whose production and career is one of the most consistent and influential in 20th century Brazilian art, Almeida & Dale sponsored the restoration of the set of sculptures and reliefs that make up the work "Templo de Oxalá", belonging to the MAM Bahia collection. The set was donated to the museum by the artist's family in 1997, at the same time as the construction of the Sculpture Park, where the Rubem Valentim Room is located.

View of "Templo de Oxalá" at the 35th Bienal de São Paulo. Photo: Levi Fanan / Fundação Bienal de São Paulo

This monumental work was exhibited partially for the first time in 1977, at the 14th Bienal de São Paulo, and presented in its entirety at the 35th Bienal São Paulo in 2023, a historic edition marked by the large representation of Afro-diasporic artists.

A self-taught artist, Valentim started painting from a young age and gained prominence in the late 1940s, when he joined a group of artists engaged in breathing new life into the art scene in Bahia. Valentim embraced the strong wave of geometric abstraction that spread in Brazilian art in the 1950s, but unlike most of his contemporaries, he took his work in a direction that was opposite to the European matrix.

![Composição nº3 [Composition nº3], 1958](https://api.almeidaedale.com.br/uploads/w_1500,f_webp,q_80/11426_A_and_D_021749_FRENTE_08a0ad657e.jpg)

Composição nº3 [Composition nº3], 1958

Acrylic on canvas

55 x 38 cm [21 ⅝ x 15 in]

“After seeing Cézanne, Kandinsky, Klee, Van Gogh, whom I liked a lot, I saw the national artists: Lívio Abramo, Bonadei, Djanira; she showed up in Bahia with an exhibition and I loved it.”

Rubem Valentim. "Rubem Valentim" catalogue, MAM Bahia, 2011 (see the catalogue here)

Immersed in the cultural environment of Salvador, Bahia − the city with the largest Black population outside the African continent − Valentim worked with the iconography of Candomblé, the instruments of worship and the symbolism of the Orixás, which he transformed into a visual language that he revisited throughout his career.

The construction process of his visual and symbolic research can be glimpsed in his study notebooks and diaries. This rich heritage was recently donated by the Rubem Valentim Institute to the Research Center of the Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand (MASP). Containing manuscripts, typescripts, letters, photos and drawings, the material consists of more than 10,000 items.

Rubem Valentim’s personal notebooks, c. 1960-61 (left) and 1958 (right) Photo: Laurent Sozzani (see the content here)

Pages from the artist’s notebooks. Fundo Rubem Valentim, Acervo do Centro de Pesquisa do MASP

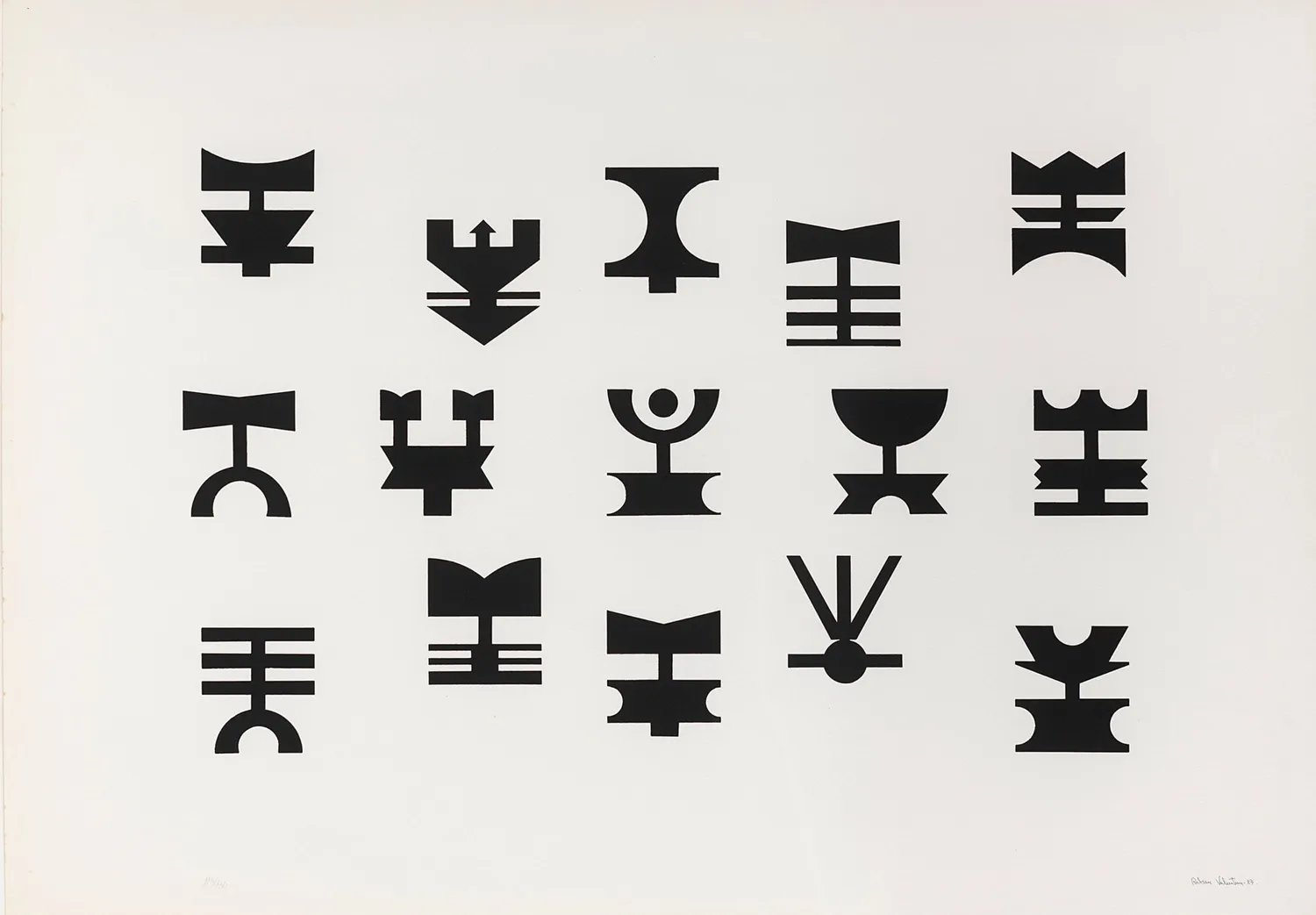

Untitled, 1987

Serigraphy on paper

70,2 x 100,0 cm [27 ½ x 39 ⅜ in]

Untitled, 1987

Serigraphy on paper

70,4 x 99,9 cm [27 ¾ x 39 ⅜ in]

“With the weight of Bahia on me—the experienced culture; with Black blood in my veins—the atavism; with eyes open to what is created in the world—contemporaneity; creating my symbol-signs, I try to transform into visual language the enchanted, magical, probably mystical world that continuously flows within me”.

Rubem Valentim. “Manifesto ainda que tardio [A Manifesto, Albeit Late]”, 1976 (read the text here)

![Forma Emblemática para Objeto - XI (Poema Visual) [Emblematic Shape for Object - XI (Visual Poem)], 1984](https://api.almeidaedale.com.br/uploads/w_1500,f_webp,q_80/2028_principal_0c11fd8c9d.jpg)

Forma Emblemática para Objeto - XI (Poema Visual) [Emblematic Shape for Object - XI (Visual Poem)], 1984

Collage on card

31 x 23 cm [12 ¼ x 9 in]

![Emblema-83 [Emblem-83], 1983](https://api.almeidaedale.com.br/uploads/w_1500,f_webp,q_80/1753_principal_86f4c504cb.jpg)

Emblema-83 [Emblem-83], 1983

Acrylic on canvas

50 x 35 cm [19 ¾ x 13 ¾ in]

Untitled, 1968

Gouache on card

34,7 x 25,0 cm [13 ⅝ x 9 ⅞ in]

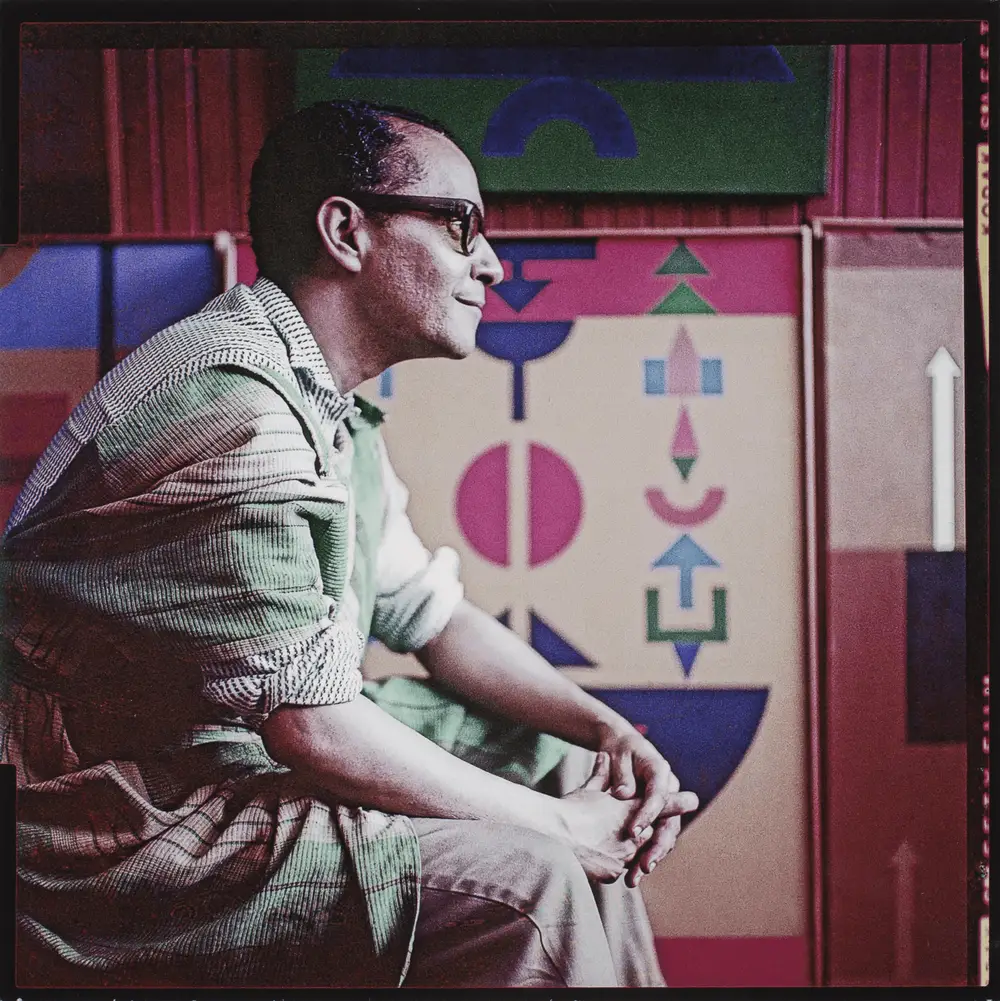

Rubem Valentim in his studio in Rome, Italy, 1965. Collection of the Centro de Pesquisa of MASP

From 1957 to 1963 Valentim lived in Rio de Janeiro, where he became assistant professor to art critic and conservator Carlos Cavalcanti teaching Art History at Instituto de Belas Artes. In 1963, he moved to Rome after being awarded a travel prize from Salão Nacional de Arte Moderna (SNAM).

With the support of Italian luminaries such as of Enrico Crispolti and Palma Bucarelli – director of the National Gallery of Modern Art in Rome, who promoted the acquisition of a work for the institution’s collection – and with the support of Giulio Carlo Argan, then president of the International Art Critics' Association – the repercussion of Valentim’s work internationally increased dramatically.

Emblema V, from the series XII Bienal de São Paulo, 1973

Acrylic on canvas

47 ¼ x 28 ¾ in

In April 1966, at the invitation of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Brazil, the artist took part in the "First World Festival of Black Arts" in Dakar, Senegal. An important moment in Afro-diasporic integration, the event marked Senegal’s then recent independence and was designed to showcase Black art productions from around the world whose aesthetics were based on principles of Blackness. In Dakar, Valentim saw his work exhibited alongside that of Black artists from across Africa and the African diaspora for the first time in his life.

In Dakar, Valentim presented a set of twelve paintings made in Rome and, together with Heitor dos Prazeres and Agnaldo dos Santos, represented Brazil among other personalities such as musicians, performers, capoeira masters and the respected Yalorixá Olga do Alaketu, mãe de santo of the Ilê Maroiá Láji Candomblé Terreiro.

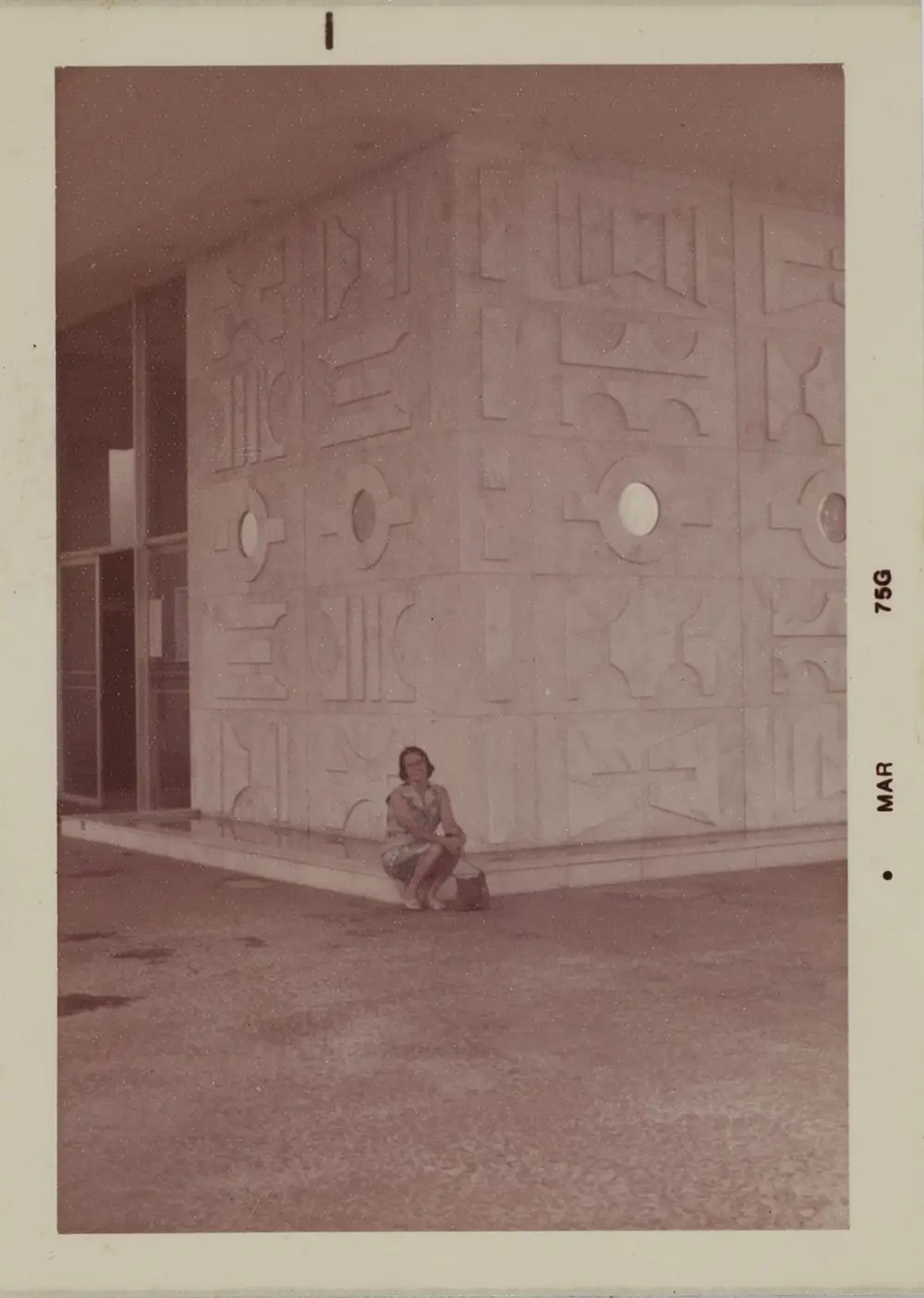

Lucia Valentim, the artist’s wife, in front of the "Painel Novacap" [Novacap Panel], in Brasília, in 1975

Rubem Valentim lived and worked in Brasília between 1966 and 1991. His arrival at the recently founded Brazilian capital followed an invitation to teach painting in one of the studios of the Art Institute of the University of Brasília (UnB), where he worked for two years. In Brasília, Valentim consolidated his technical and poetical research on geometric constructivism and the symbology of African cultural legacy. His relationship with Brasília is indelible and it was also here that he deepened the third-dimensional element of his work, motivated by the amplitude of the city’s architectural spaces.

“We must recognize an ambitious plan that consisted of negotiating a double nationality: to be modern while still being Afro-Brazilian, to be Brazilian without abandoning Blackness”.

Lisette Lagnado. “The return and confirmation of Rubem Valentim”, 2018 (read the article here)

It was in the federal capital that Valentim was commissioned to produce his first public work, a 1972 marble mural that adorns the façade of the headquarters of Novacap, the building that currently houses the State Secretary of Economy of the Federal Capital Government. In 1978-79, Valentim designed another public work, which he entitled as "Marco sincrético da cultura afro-brasileira" (or Syncretic Landmark of Afro-Brazilian Culture). The massive concrete sculpture was installed in Praça da Sé, in the city center of São Paulo.

Installation of "Marco sincrético da cultura afro-brasileira" in Praça da Sé, in 1979. Photo: Silvestre Silva

Going beyond the mere formalistic use of religious images, Valentim maintains the connection between these emblems and their origins, reinforcing the link with the meanings they manifest, such as protection, sexuality, birth, death, rebirth, the cycle of life and nature. The symbolism of the vertical and horizontal planes, linked respectively to the divine and the human realms, as well as the use of colors related to the Orixás, are also central to his work.

![Emblema II [Emblem II], 1987](https://api.almeidaedale.com.br/uploads/w_1500,f_webp,q_80/11060_FRENTE_dae8a0dbfa.jpg)

Emblema II [Emblem II], 1987

Acrylic on canvas

50 x 35 cm [19 ¾ x 13 ¾ in]

![Emblema-78 [Emblem-78], 1978](https://api.almeidaedale.com.br/uploads/w_1500,f_webp,q_80/15763_FRENTE_212a59d7df.jpg)

Emblema-78 [Emblem-78], 1978

Acrylic on canvas

101 x 74 cm [39 ¾ x 29 ⅛ in]

“Intuiting my path between the popular and the scholar, the source and the refinement—and after having created some compositions, already quite disciplined, with ex-votos, I began to see in the symbolic instruments, in the tools of Candomblé, in abebês, in paxorôs, in oshes, a type of “speech,” a Brazilian visual poetics capable of adequately configuring and synthesizing the whole nucleus of my interest as an artist. What I wanted and continue to want is to establish a “design” (which I call Brazilian Linework), a structure capable of revealing our reality—mine, at least—in terms of a sensitive order”.

Rubem Valentim. "Manifesto ainda que tardio” [A Manifesto, Albeit Late], 1976 (read the text here)

The creation of a space of spiritual vibration is an act that also underpins the works in the series "Emblemágicos" (or Magic Emblems), which arose from Valentim’s fascination with the pontos riscados [sacred signs] of Umbanda, a religion he learned about when he lived in Rio de Janeiro.

Emblemágico-84, 1984

Acrylic on canvas

50 x 70 cm [19 ¾ x 27 ½ in]

“The constant allusion to the symbols, in Umbanda and Candomblé, of Exu and Xangô, deities of communication and of justice, respectively, suggest that we see Valentim’s work as a public manifesto for social equality, thus underscoring its political dimension”.

Roberto Conduru. “Albeit Late, But on the Eve – Rubem Valentim and Time”, 2018

Interested in creating an artistic language that was fundamentally Brazilian but not nationalist, one that synthesized all the nuances of this identity, Valentim kept an eye open to the universal and made his work a constant investigation of the world and of his own place in it. He studied the sacred practices and culture of Indigenous America and various non-Western civilizations. Gathered in this selection of works, Valentim’s constructions renew the age-old union of art with the intangible and the sacred in all their forms.

“An examination of the themes of space, futurity, and championing Black equality suggests Afrofuturism’s suitability to a critical reading of Valentim’s plastic works and 1976 manifesto”.

Kimberly Cleveland. “Rubem Valentim: Early Afrofuturist Expression”, 2021 (read the article here)

![Emblema 86 [Emblem 86], 1986](https://api.almeidaedale.com.br/uploads/w_1500,f_webp,q_80/0035_principal_a42bb3b0cb.jpg)

Emblema 86 [Emblem 86], 1986

Acrylic on canvas

41 x 27 cm [16 ⅛ x 10 ⅝ in]

![Emblema 89/90 [Emblem 89/90], 1989/1990](https://api.almeidaedale.com.br/uploads/w_1500,f_webp,q_80/1752_FRENTE_d4f3f31ebb.jpg)

Emblema 89/90 [Emblem 89/90], 1989/1990

Acrylic on canvas

50 x 35 cm [19 ¾ x 13 ¾ in]

“Brazilian art can only be an authentic poetic product when it is the result of syncretism, of acculturations (nonverbal semiotics/semiology) of the signs from the cultures that form the basis of our nationality (white-Portuguese-Black-Indian) in additional to the contribution of cultures recently brought by the different peoples of other nations and that, here in this space Brazil-Continent, common to all, are mixed to create a system of cultural Brazilianness of singular character, of rite, myth, and rhythm that are unmistakable despite the infamous Global-Tribe. The fundamental thing is to assume our identity as a people in terms of the Nation”.

Rubem Valentim. “Manifesto ainda que tardio" [A manifesto, albeit late], 1976 (read the text here)

Untitled, 1991

Acrylic on canvas

35 x 50 cm [13 ¾ x 19 ¾ in]